Imagine an organization with a name recognized in every country in the world, whose every move was watched by hundreds of millions of people, and whose successes fulfilled the dreams of a nation and inspired awe and admiration around the world. This was NASA in the 1960s.

I was five years old when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first men to land on the Moon during the flight of Apollo 11. Like many people, I watched the event on a black and white television, and then went outside to look up at the Moon, knowing people were there. For the millions of children across the globe who were inspired by that occurrence, this was a defining brand moment for NASA.

The Apollo program set a new and dramatic benchmark for our abilities as a nation. If we can go to the Moon, then what other feats long considered impossible could we accomplish? While President Kennedy’s 1961 announcement to send humans to the Moon was primarily political, it became a driver for imagination, scientific discovery, and engineering.

The research and development underpinning the Apollo program presented many challenges that called for new solutions. These solutions influenced the growth of high-technology industries and ultimately thousands of products were spun-off into new commercial markets, such as semiconductors and computers, microwave ovens, batteries, cordless power tools, kidney dialysis machines, MRI and CAT scans used in healthcare, solar panels, fire-retardant fabrics, polarized sunglasses, water purification, advances in food preservation, improved satellites, and more. Studies indicate a societal return on investment as high as 14 dollars for every dollar spent, causing the returns on most other forms of investment to pale in comparison.

Despite Gallup’s research showing that over half of the American public didn’t want to fund the lunar landing goal, the Moon landings boosted the level of national pride as an estimated 530 million people came together for a brief moment to watch the events unfold on television. This was no small feat considering the country was still dealing with repercussions related to the assassinations of President Kennedy, his brother Robert, and Martin Luther King, Jr., an unpopular war in Vietnam, the possibility of nuclear annihilation, a stagnating economy, and social unrest across the country.

This new national pride combined with the high media profile of the Apollo program and its achievements inspired a generation to become excited about STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math). The data clearly shows higher and steadily growing levels of technical education in the years following. This generation would go on to harness the micro-electronic technologies developed during the Apollo program to wire, connect, and automate society in completely new ways—people such as Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, and Elon Musk.

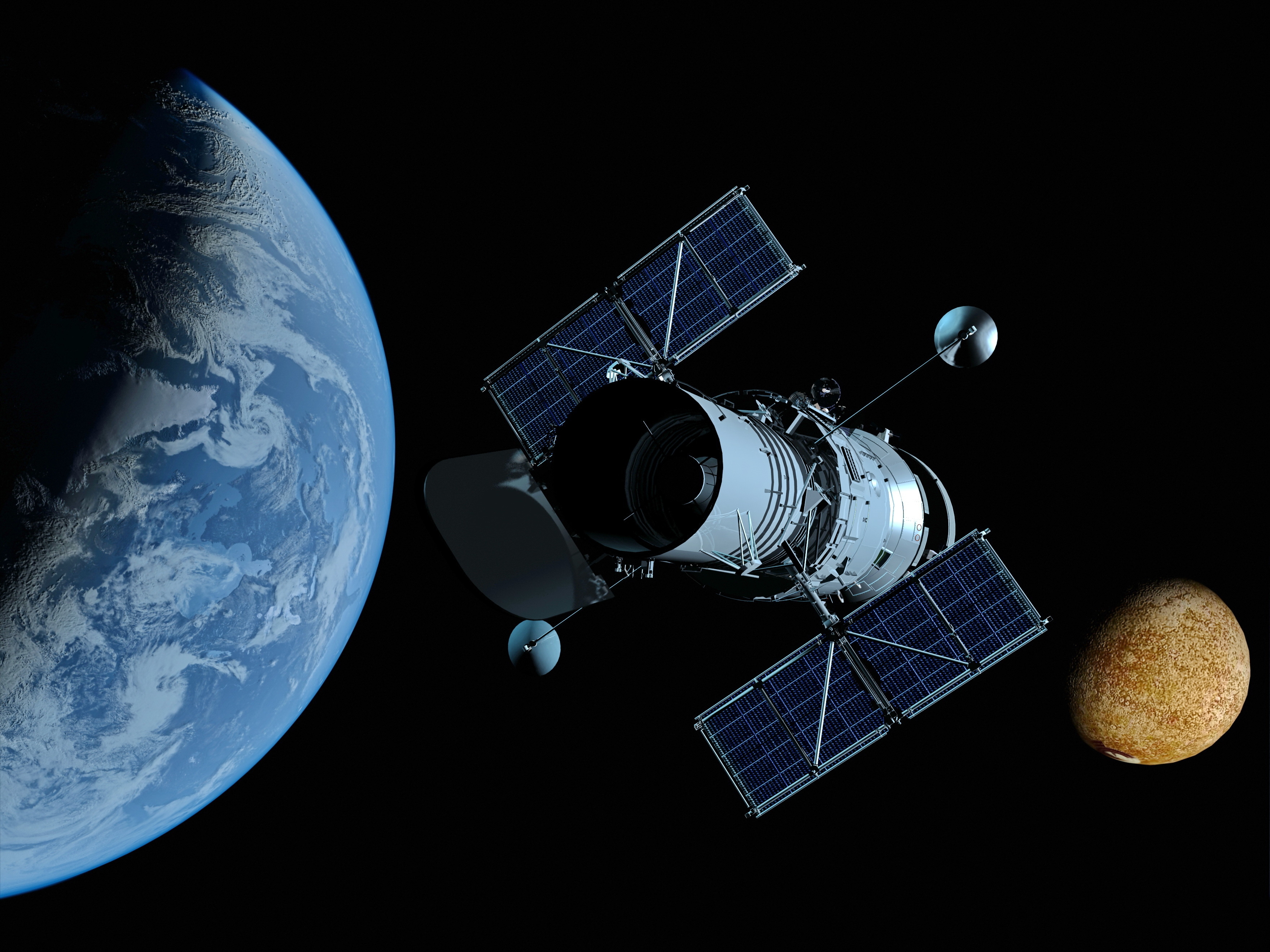

The Apollo program also forced people to view Earth differently. The famous Earthrise photo taken by the crew of Apollo 8 in 1968 forever changed our perspective. For the first time, we saw our tiny, fragile planet sitting in the darkness of space, which focused our energies in new and unprecedented ways. This was later driven home by “The Blue Marble,” another famous distant image of Earth taken four years later by the crew of Apollo 17. As Bill Anders, the Lunar Module Pilot for Apollo 8 who snapped the Earthrise photo, once said during an interview, “After all the training and studying we’d done as pilots and engineers to get to the Moon safely and get back… what we really discovered was the planet Earth.”

Fifty years have since passed, and the Apollo program no longer has the impact it once had. Surveys continue to show an eroding connection between Apollo and the public, especially with younger people. Members of Generation X and Millennials believe in growing numbers that the Moon landings were faked––from four percent 50 years ago as the landings were actually occurring to as high as 25 percent in some recent surveys. This view is exacerbated when current celebrities and athletes who have a tremendous influence on young people also publicly adopt this view. Sadly, what was one of our crowning achievements is slowly turning into a distant memory, or even worse, an indictment against government and how far it will go to achieve some imagined sinister agenda.

Having seen countless believers trying to convince nonbelievers the Moon landings were real, I’ve reached the conclusion that we, as a group of space advocates, leaders, and enthusiasts, may be missing a critical point. Regardless of why a growing number of people don’t believe, few dispute the amount of effort that went into the program—America’s finest corporations and universities working tirelessly with NASA to research, design and build the Saturn V (one of the largest, most powerful machines ever built), new communications systems, tools, test equipment, and other critical infrastructure and materials. That effort generated most of the positive outcomes of the Apollo program. However, it’s also where the least amount of attention tends to be focused.

While most of the world only ever saw young, white male astronauts and members of mission control in the media, the engineering effort of almost a half-million people of both genders, and many races and cultures, directly touched people’s lives through the Apollo program’s huge economic impact and generational inspiration. While humans walking on the Moon was a seminal moment in our history, I believe the process of striving to get there was the most important aspect of the lunar landing program.

According to a 2018 study by the Pew Research Center, about 90 percent of those who are well informed about space news believe it is essential for the U.S. to continue to be a global leader in space exploration. That number drops significantly for those who haven’t paid much attention. Similarly, 75 percent of those who are well-informed and attentive to space news believe basic scientific research should be a top priority for NASA, versus a mere 31 percent for those who aren’t. NASA has a public brand problem. With the beginning of a new age of space exploration led by the likes of Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos, NASA must continue to stay relevant in the minds of today’s youth through continued space research and the resulting positive economic impact. In other words, NASA must somehow directly touch people’s lives.

Basic marketing theory suggests that for an organization to have an impact and cut through the noise, it must make an emotional connection with people in the simplest possible way. Public opinion polls have already shown how an emotional connection can impact the public view of NASA and space-related activity. Space historian Roger Launius has noted that movies such as “Apollo 13,” “Armageddon,” “Deep Impact,” and “The Martian” appear to have buoyed interest in space exploration and shifted public sentiment in a positive way. In the same manner that movies can create an emotional connection, NASA and its supporters must adopt methods to more regularly connect with average people, not just those who are interested in space.

People tend to gravitate towards the people, companies, and organizations they like—but what drives likability? It’s the positive emotion and the experiences that come with it. Creating that emotion is often as simple as telling the story behind something, which creates a higher degree of authenticity and likability and allows people to more easily connect with it. One of the reasons SpaceX, Blue Origin, and Virgin Galactic tend to be more likable is because of the stories of Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and Sir Richard Branson. Their stories are frequently shared in the media, which provides people a point of connection when they hear about rocket launches, booster landings, and Tesla Roadsters orbiting Earth. As leaders, they also serve as the evangelists behind their efforts. This builds trust, creates loyalty, and generates advocacy.

For people to connect with a brand, it must have a genuine and personal story. They need to have positive experiences with the brand and know their voices are being heard. While NASA has made positive strides by making both the Kennedy and Johnson Space Center experiences more interactive and visually stimulating, they need to do much more to convey their story. They should put their visual failures (Apollo 1, Challenger, and Columbia) humbly front and center and in great detail explain what was learned. They should grow their outreach to include more K-12 institutions to create lasting positive experiences with as many children as possible. With every new product released to the market that uses a NASA-generated idea or innovation, the development, however small, must be added to the larger narrative so that people will see how NASA directly affects and improves their lives.

While there’s obviously much more NASA could do, it is critical for all of us—space advocates, leaders, and enthusiasts—to become brand evangelists, working together to help the general public understand NASA’s powerful impact on all of us. With the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 upon us, now is the perfect time to share with everyone—whether they believe we actually landed or not—how the process of planning and designing a trip to the Moon has made our world a better place.

This piece originally appeared on A Step Beyond: The Blog and was published in the National Space Society’s publication, adAstra.