Episode 214

[easy-social-share buttons=”facebook,twitter,google,linkedin,mail” counters=1 counter_pos=”topm” total_counter_pos=”leftbig” style=”icon_hover”]

You are agency owners, not career keynote speakers. But that does not mean you don’t earn your living as a presenter. You present every day of your professional lives. You hold one-on-one meetings in your office and lead all-agency meetings. Some of you are speaking at conferences and tradeshows as well.

By sharing your expertise, teaching, and demonstrating that you know your stuff, you will create biz dev opportunities that start deeper in the funnel. It doesn’t matter if public speaking is a strength or a source of anxiety, it is a learnable skill where craft outranks natural talent.

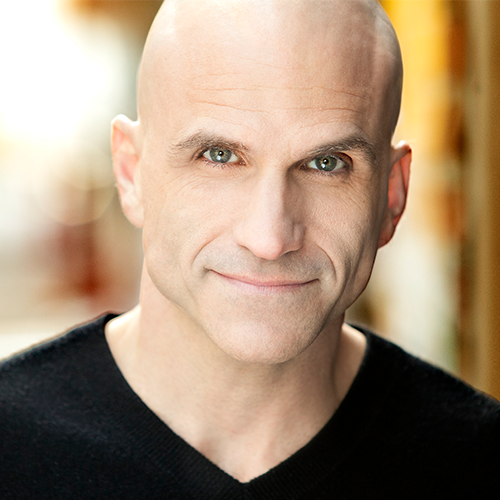

My guest Michael Port has written six best-selling books including Book Yourself Solid and Steal the Show. He has spent the last several years developing and honing the company he co-owns with his wife Amy, Heroic Public Speaking (HPS). HPS conducts training programs for speakers of all walks of life. When I think about great public speakers that are commanding top fees for keynoting, almost all of them have gone through some level of training with Michael and Amy. But they also train people who will never step on a formal stage, but just want to present their ideas in a more compelling way.

The people who go through the HPS program develop confidence and the ability to command an audience. Michael joins us on this episode of Build a Better Agency to talk about the art and science of presentation. He explains how we can use it to serve our agencies, our teams, and our clients in bigger, better ways.

A big thank you to our podcast’s presenting sponsor, White Label IQ. They’re an amazing resource for agencies who want to outsource their design, dev or PPC work at wholesale prices. Check out their special offer (10 free hours!) for podcast listeners here: https://www.whitelabeliq.com/ami/

What You Will Learn in this Episode:

- You are presenting and public speaking every day

- Why speeches are an unrivaled biz dev opportunity

- Michael Port’s story, and the work he and his wife Amy are doing with Heroic Public Speaking

- Why presenting is a combination of art and science

- How mastery of public speaking will enable you to become a more effective agency owner

The Golden Nugget:

“If your life can change for the better by improving your ability to communicate, it makes sense to develop that craft.” @michaelport Share on X “During a presentation, authenticity and naturalism often come from preparation.” @michaelport Share on X “A lot of great speeches lie at the intersection of educational content and theatrical elements.” @michaelport Share on X “Whether you are sitting across the table from an employee or standing on-stage at a national conference, all of you present every day.” @DrewMcLellan Share on X “A lot of great speeches lie at the intersection of educational content and theatrical elements.” @michaelport Share on X “One of the big problems that we often encounter with speeches is that people bring too much plane for too little runway. They bring content for an entire day and attempt to deliver it in 45 minutes.” @michaelport Share on XSubscribe to Build A Better Agency!

Ways to Contact Michael Port:

- Website: https://heroicpublicspeaking.com/

- Twitter: @michaelport

Speaker 1:

It doesn’t matter what kind of an agency you run, traditional, digital, media buying, web dev, PR, whatever your focus, you still need to run a profitable business. The Build a Better Agency Podcast presented by White Label IQ will show you how to make more money and keep more of what you made. Let us help you build an agency that is sustainable, scalable, and if you want down the road sellable, bringing his 25 plus years of experience as both an agency owner and agency consultant, please welcome your host, Drew McLellan.

Drew McLellan:

Hey everybody, Drew McLellan here with Agency Management Institute. Welcome back to another episode of Build a Better Agency. If you are a regular listener, thanks so much for coming back. If you are a first time listener, welcome. My goal is two things, one, to get you thinking a little differently about your agency and the decisions you make around running it to be more scalable, more profitable, a little more fun, and also to give you very actionable content that you can actually take notes on if you want to, not if you’re driving or on a treadmill. But anyway, you can grab notes from each episode, and you can put some of this into play.

Sometimes putting it into play means doing something differently. Sometimes it means starting something new, and sometimes it means stopping something that maybe you shouldn’t be doing any more. But anyway, that’s my goal is to bring amazing guests who will help you think differently about your business. And boy, do we have one of those guys today. Before I tell you about our guests, just a couple things. Number one, if you have not registered for the Build a Better Agency Summit, I’m telling you, it is going to be an amazing two days of conference, of networking, of learning, all very focused on the business of running your business that happens to be an agency.

We’re going to talk about profitability, we’re going to talk about Biz Dev. We’re going to talk about trends in the industry, we are going to talk about how to break out of imposter syndrome if you struggle with that, we are going to talk about how not to get yourself into legal trouble if you are doing influencer marketing. The topics and the content and the speakers are just amazing. I have called in all kinds of favors to really stack the deck for the 2020 Build a Better Agency Summit. It’s in May, May 19th and 20th in Chicago.

And if you haven’t grabbed your ticket, they are not going to get any cheaper as we get closer to the event, so please grab your ticket now and join us because it’s going to be really awesome, and I fear it’s going to sell out, so please don’t wait too long for that. Also, just a reminder that every month, we give away a free workshop, either a live workshop or one of our on demand courses for folks who are leaving us ratings and reviews whether it’s on Stitcher or Google or iTunes, wherever it is you may be, just leave us a review, doesn’t even have to be a nice one. Leave us a review and take a screenshot of it and shoot me an email because I can’t tell who it is if I just go look at the reviews, which I do, I read them pretty consistently and take them to heart.

But if your username on iTunes is Biker Dude 12, I don’t know who that is, so take a screenshot and shoot me an email. All right, let me tell you a little bit about the topic today and our guests. So one of the things that I know is true, a couple things that I know are true. Number one, each and every one of you gives a presentation pretty much every day of your professional life, either you are talking to one employee in your office, you are doing an all agency meeting.

Or for some of you, you have caught on to what I know which is fact number two, which is when you stand on a stage and you share your expertise, you teach, you help, you demonstrate that you know your stuff, that is a brilliant Biz Dev opportunity for you, that is a great way for you to have a third party, a conference, a trade show, an association, give you credit for being a subject matter expert, and then you step on stage and you’re super helpful and you help that audience be better at their job. And from that comes incredible opportunity.

So whether you’re sitting across the table from an employee, or you’re standing on a stage at a national conference or convention, all of you present every day. And I know for many of you this is a craft that you keep working on. For others I know this is an area of anxiety and something that you think you’re just not naturally good at. And so I have an amazing guest today, and we’re going to dig into all of that. So let me tell you a little bit about Michael Port. Many of you are probably familiar with Michael, you probably read one of his six books.

One of my favorites is called Book Yourself Solid, which is written back in like 2008 when I first met Michael, and there have been several edition updates, since then. He also wrote a great book called Steal the Show, which is more about presenting, Book Yourself Solid is about bizdev, and how to create relationships and get invited into opportunities. Both, great books, I highly recommend them. But in the last several years, Michael has honed his focus in terms of his profession and what he does all day, and he and his wife, Amy have put together an organization called Heroic Public Speaking. And it is amazing.

So when I think of all of the great public speakers that I see at conferences that are doing keynotes, the subject matter experts at an industry level, almost all of them have gone through some level of training at HPS. And they walk away, transform, they walk away raving about the experience, about their confidence level, about the ability to command an audience, whether it’s an audience of one or 1000. And they credit Amy and Michael and the organization they’ve put together and the training they do for helping them really change how they view speaking, how they use speaking for their business, and how they approach the audience and the experience of speaking.

And so I’ve never, ever, and I have dozens of friends and colleagues that have gone through this training. And there are different levels of training, but I have dozens of colleagues who have gone through it. And I’ve never heard anyone say anything other than it exceeded every expectation they had and they walked in with high expectations, and it was really a remarkable experience. And so I’ve known Michael for years, and I wanted to get him on the show and pick his brain about how we as agency owners and leaders can think about the art of presenting, which I think he’s going to tell you is not really just art, but it’s a combination of art and science, and how we can get better at it so that we can serve our team and our agency and our clients in bigger, better ways. So let’s just jump right into that conversation. So without further ado, Michael, thank you for joining us. Glad to have you on the show.

Michael Port:

It’s my pleasure. Thank you for having me.

Drew McLellan:

So we have known each other for eons, and you have certainly shared your expertise in a variety of different ways. But for the last many years, you and your wife, Amy have been leading the charge with Heroic Public Speaking. So I suspect there was a lot of thought that went into that particular name. So tell us how you came to that because I think it probably speaks to how you think about speaking.

Michael Port:

Yeah, we actually came up with that name at dinner in Annapolis, Maryland, after taking our kids to a comic book shop to look for comics. And we immediately knew that we had no intention of branding ourselves in a traditional sort of superhero fashion.

Drew McLellan:

No tights for you, is that what you’re saying?

Michael Port:

No sir, no tights for me. I don’t think my audience is interested at all in tights. But we do believe that great speeches change the world. You can look at critical moments in history, and very often there is a speech or a number of speeches that produced some sort of social change, people thought differently, acted differently, or felt differently as a result of that speech. And we also think that giving a great speech is a heroic act, because it often takes great courage, you’re going to make big choices, try new things. Now often put yourself on the line in a way that you haven’t before. And through that process, not only can you change the world, but you can change yourself. So that’s why this concept of heroic public speaking was so profoundly important to us and we find that our students feel the same.

Drew McLellan:

Yeah, I love that. But for the listeners, who probably… For most of my listeners, they’re not ready to hit the road and be a keynote speaker. They’re not thinking that they’re going to be doing a TED talk, although some of them may aspire to that. You also don’t think of speaking as a, you have to be on a keynote stage to have significance, to have that speech have, or presentation have a lot of meaning. And I know a lot of the work that you do is not really with traditional speakers, but with corporations and internal teams as well. So can you talk a little bit about sort of how you view speaking from that lens?

Michael Port:

Yeah, every once in a while, we’ll be talking to a company about working with them, and someone on the committee will say, “Yeah, but we don’t really do public speaking.” And I’ve heard that more than once. And it’s something that I find interesting, because I think anytime sound is coming out of your mouth, unless, of course, you’re in your car by yourself or in the shower by yourself, you’re doing some form of public speaking. And most people, especially agency owners are trying to change the way people think, feel or act. Let me say that again, think, feel or act.

And if you look at your day, regardless of what role you’re in, it’s very likely that there are moments throughout that day where you’ve got to get either someone who works with you, or for you to change the way they feel, to change the way they act, to change the way they think. Or if you’re trying to book more business, you’re going to try to get those potential clients to change the way they think, feel or act so they do business with you.

And the same thing is true when you’re proposing new ideas to your current clients, you want them to change the way they’re thinking or feeling or behaving, so that you can produce better results for them. So this is something we do all day long. And it may be in one-on-one conversation. And it may be one to three or one to 30 or one to 300 or one to 3000. Either way, it doesn’t make a difference. Our objective is still the same. We want to change the way people think, feel and act. And it’s likely that most people who are up to big things do that.

Drew McLellan:

Yeah. Yeah. So I’m curious, do you believe that if someone becomes a better oral presenter, however they may be doing that, does it also impact… Because I think about agency owners, and oftentimes, they’re trying to be influential with their words, but sometimes it’s coming out of their mouth, and sometimes it’s the written word.

Michael Port:

Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Drew McLellan:

Do you think learning how to be a better presenter or speaker shows up in how I write as well?

Michael Port:

Well, I think so. They’re not exactly the same thing.

Drew McLellan:

No, of course not.

Michael Port:

And very often what happens is, when somebody tries to improve their public speaking, one of the first things that is helpful to them is to move away from a writing style that is more traditional and academic into a writing style that supports the spoken word because you can take a great novel, and attempt to read it on stage, it’s going to feel like a novel, it’s not going to feel like a speech. So you might start out a sentence in a book with something like June. 1972. It was dark. But it’s unlikely you’re going to walk into a meeting when you’re leading a new initiative at the office and say, “June 1972, it was dark.”

You wouldn’t say that, you’d say, “Listen, I remember it was June, I think of 1972. I remember, it was really dark,” just in the way that we would normally talk or express ourselves. So very often, we have to move our language from this more traditional academic approach to the spoken word, which takes some adjustment.

Now, it also can be helpful on the page if you are… Or a web page or written page if you’re trying to write copy, you want to write copy that makes the reader feel like it’s a real person and it is talking to them, and then it’s not speechified in the writing itself, either. So it’s a balance, but I think anything that we can learn to improve our ability to communicate is going to make a difference, whether it’s in the written word, or the spoken word. They’re just slightly different mediums, and we take a slightly different approach to each one.

Drew McLellan:

Yeah, I was thinking about as you construct a great presentation, that thought process of construction probably lends itself well to the written construction of a message or-

Michael Port:

It does.

Drew McLellan:

Yeah.

Michael Port:

Yeah, it really does.

Drew McLellan:

So we’ve all heard the old idiom of that people would rather do anything rather than speak and the second fear after death or something awful. For me, it would be way down there after snakes and height.

Michael Port:

Well, just for the record, that is a myth actually.

Drew McLellan:

It is, okay.

Michael Port:

Yeah, it’s easy to pull out of your pocket and say, “Oh, yeah, well, public speaking is the number one fear even over death.” I mean Jerry Seinfeld has a great joke, he says that, “If that’s true, that means that if you’re at a funeral, you’d rather be in the box than giving the eulogy.”

Drew McLellan:

Right, right.

Michael Port:

So I think if you said to most people, if I said, “Listen, Drew, you’ve got two choices right now. You could die or you could give a 10 minute speech to a couple 100 people, but you have to decide right now.” Most people are going to choose to make the speech. I don’t think most people will say, “Yes, please kill me now.”

Drew McLellan:

I would hope so, I would hope so.

Michael Port:

What came out of that study was something different. It was just that fear of death is not a fear that people have on a regular basis. We don’t feel that close to death until we are certainly at an age or in a situation where that might be the case. But we are every single day confronted with the need to get up and present ourselves in some way. So it’s just a more present fear. It’s not actually a greater fear, and that’s the true difference.

Drew McLellan:

Yeah, and it seems to me that part of what makes people so anxious about speaking is, I hear a lot of people say, “Well, you know what? I don’t have that gift. I’m not a great speaker.” And I know that for you and your team, your belief is and I share it is that speaking is a craft, it is a skill that you can get better at with the right instruction and practice and all that. So talk a little bit about the dichotomy of those two ideas and what guys landed.

Michael Port:

Yeah, so look, it much like any discipline. If I want to get better at say, basketball, I can train and I can practice, and I can get a lot better. I will never play NBA level basketball. It’s just I don’t have the DNA for it nor do I have the desire for it. But I can certainly get better at basketball. And the same thing is true for public speaking, it is a craft, and you can learn the craft, which will help you get better at it. And yes, some people may have some more natural talent, but I think most successful people will tell you that talent only takes you so far. And I’m sure you know a lot of people with a lot of talent that went wasted often because of the voices inside their head that for some reason told them they weren’t good enough, or they didn’t know enough or they just weren’t enough in some way. So they didn’t leverage the talent that they had.

So the question is, what are your goals? I think that’s really the question. Meaning, if your life can change for the better in some way by improving your ability to communicate, then it makes sense to develop that craft and to work on it. But if it’s not really important to you, then I would never encourage somebody to work on it. It just wouldn’t be a top priority. So sometimes it looks like magic when people are performing but it’s really not its craft. I mean, if you look at Meryl Streep, Meryl Streep has a lot of natural talent. But what she has even more than natural talent is craft.

If you look at Tom Hanks, same thing, craft. Now, in order to know that you have to know the craft because then you can see the craft. If you don’t know what to look for, then you think it’s all just natural talent, just a gift that they possess that other people don’t. And that’s one of the things that’s most remarkable. Actually, do you know Jordan Harbinger, he’s a podcaster?

Drew McLellan:

I don’t.

Michael Port:

So Jordan Harbinger used to be the host of a podcast called Art of Charm, and now he has the Jordan Harbinger Show and they get a few million downloads a month. It’s a very big podcast, very successful podcast. And he feels very comfortable for the microphone. But a number of years ago, he came to one of our events because he didn’t feel as comfortable on the stage. This is a different medium. And he saw me do a masterclass where I took the student, had them do about five minutes of material on stage, and then I coached them and directed them the way a director would work with an actor, exact same thing. And there’s a very specific process to it. And so the transformation was quite quick and quite-

Drew McLellan:

Dramatic

Michael Port:

… dramatic, I think is the right word. Yes. Thank you. Very dramatic. And I remember Jordan later on said to me, he said, “Michael, I gotta say when I first saw that happen, I was really pissed off.” I said, “What do you mean?” He said, “Well, I flew all the way across the country from California to attend this event and I spent some money and someone got on the stage and,” to use his words, he goes, “They were really bad and they got really good in like 10 minutes. That’s just impossible.”

So I thought, “I can’t believe I just flew across the country, and these people have staged this before and after thing. And then you did another one a little later in the day, and I couldn’t believe.” He did the same thing. And I kept thinking, “How much time does it take to rehearse this to make this look like it’s not staged? Because that’s incredible. Then I saw you do it again and again, and I started to realize, oh, wait, this is not staged, this is actually happening, I realized that there’s a process that you’re using with each person, and it’s slightly different depending on the person because there are no formulas that make this work. It’s process oriented. And those two things are different because each individual brings different things to the stage, so to speak.” So each person is going to get different advice from us, depending on what they need.

But then he became a student of ours, and we worked with him for a long time, and he’s become very successful on the stage as well as behind the microphone. But often, it does look like magic, so much so that it doesn’t seem like it could be real. That’s only because you may have not been in an environment where performers transform quite quickly. And so for us, my wife and I both have master’s in acting, Amy from Yale, and I did my masters in acting at NYU. And we were used to that, that’s just what you do every single day, you somehow transform, you change, you’re very, very willing to make big choices and try new things as a regular way of being.

And that that’s one of the things that I love about this is that it’s so individual, is that there is no formula, and then there is no one way to do it. But there are processes. And if you do understand the processes, and you trust the processes, and you give yourself the time to work through the processes, you’re going to come out in a much stronger place with a lot more confidence because you mentioned before this fear that people have, where does it come from? Why are we afraid of it? We know we’re not going to get hurt.

Drew McLellan:

Right, and no one’s going to throw anything at us odds [crosstalk 00:21:56].

Michael Port:

No, I’m not sure that’s not going to happen. Maybe, if you’re the president of the United States, I’m going to throw a shoe at you [crosstalk 00:22:04] at some point. But I fell off the stage once and I didn’t even get hurt, so it’s very likely we’re actually going to get hurt physically. So what are we afraid of? We’re afraid of the rejection. Maybe someone tells us, well, they don’t like our ideas. Maybe they don’t laugh at our jokes. Maybe people just look uninterested.

Drew McLellan:

I was going to say, I think that’s the biggest fear, that you’re going to bore people or not be interesting.

Michael Port:

Yeah. So here’s what happens. We then focus on approval, rather than producing results. So if we’re very hyper aware of the possibility of some sort of rejection, then what do we do? Well, we design a presentation to get approval. So we might pander to an audience or we might not really say what needs to be said, or maybe we don’t work that hard on the presentation because we’re afraid that, well, if I really do work hard on it, and it doesn’t go well, what does that say about me? That means I’m even worse than I thought I was. But if I go in there and wing it, and it doesn’t go great, I can always say, “Well, I didn’t work that, I didn’t prepare that much. I just winged it, so that’s probably why it didn’t go that well.” It gives us a nice out, it gives us an excuse.

Drew McLellan:

Yeah.

Michael Port:

So our job is to focus on results. So what do we do? We get really clear on our objectives. Well, what are we trying to do with this particular presentation, regardless of whether it’s on a stage or boardroom, conference room, or just a meeting with a couple people,, what’s our objective? All right, well, if we know our objective, then we can choose tactics that will help us pursue that objective. Now, what kind of tactics do we want to choose? We want to choose tactics that will help people feel differently, think differently, or act differently, simple.

Now, that takes some time, it takes some work. We don’t always know exactly what is going to affect people, but the more rehearsal that we give it, the more that we do it in front of actual people, the easier it is to determine what is going to produce the change that we want to produce.

Drew McLellan:

As I’m listening, I’m thinking, I will bet you dollars to donuts that most of the people listening, who step on a stage at a trade show or step in front of a client or a prospect or even stand in front of their entire agency for an all agency meeting either don’t rehearse it all, or certainly don’t rehearse in front of other people.

Michael Port:

Yes. So here’s the thing. We’ve been told more than one time by very, very well meaning people, that rehearsal doesn’t work. They said, “I’ve tried it, it doesn’t work.” Now, I think they’re right because what they’ve tried is the following, a little bit of rehearsal, such that when they’re actually performing, instead of being in the moment, what’s happening is they’re trying to recall what they did in rehearsal. And because it’s not in their body, meaning it doesn’t come to them quickly, they feel slow and stiff, and they’re having trouble trying to recall it, so they just feel off their game. And they say, “Listen, normally, I’m really good, quick on my feet, I got the gift of gab, I’m charming, and I couldn’t be because I rehearsed, it made me stiff.”

So the problem wasn’t rehearsal, however, it was not enough rehearsal, because they’ll feel better if they don’t rehearse at all, but they may not actually achieve their objective. But if they only do a little bit of rehearsal, they won’t feel very good, and they likely won’t achieve their objective either. If they do a lot of rehearsal, they’ll feel really good, because they will be able to do what they intend on doing, and they’re much more likely to achieve their objective. Now, even if they don’t achieve their objective, they can still feel good about themselves because they know they did the work.

And I think most people who are ambitious people, who are aspirational people, who are accomplished people do not like doing things half baked, yet, they will do their public speaking half baked. And so that’s a bit of a conflict for them. So once they start to take a different approach, and they see that it works, well, then they’re off to the races because when you do something, and it works, you just want to do more of it.

Drew McLellan:

Right, so I want to be very clear listeners, he is not advocating don’t rehearse at all, because it’s better than rehearsing a little bit. Do not come to me when I see you next and say, “You know what? When Michael Port was on your podcast, I realized that I don’t have to rehearse at all,” that’s not what he said. Even though you want it to be what he said, it is not.

Michael Port:

Yeah, look, at Heroic Public Speaking, we’re pretty rigorous training organization. We don’t really do patch jobs, we’re not into the band aid fix. We work with people that really want to make a difference in the world and are willing to put some time and effort into up leveling their skills. So the amount of rehearsal that you give to something, however, I think should be proportional to the stakes of that situation.

Drew McLellan:

Sure.

Michael Port:

If it’s low stakes, why spend a lot of time on it, unless you just enjoy it, spending time on rehearsing. But if the stakes are very high, it seems like that would require more rehearsal. When the Navy SEALs go into into battle, or they go on a particular mission, does anybody think that they’re winging it?

Drew McLellan:

Right, right.

Michael Port:

I mean, think about it this way-

Drew McLellan:

And would you want to be one of the guys on the squad if that was the case?

Michael Port:

Oh, my gosh, probably not. They’re in there improvising very often, because situation on the ground will change, but what they’re able to do is fall back on their training, because in the military they say you’re not going to rise to the occasion, you’re just going to fall back on your training, because the higher the stakes, the higher the stress, the harder it is to supposedly rise to the occasion. And if you are well trained, it gets much easier because you can fall back. Now, think about this Drew, imagine someone said, I’ll just use myself as an example because I know that I will fail miserably if I was asked to do this.

But if somebody said, “Listen, Michael, I have a squad right now going into Syria, and we have a really, really high stakes mission, we have to rescue some hostages. And I know you have no training in how to do this whatsoever. I know you don’t even know how to use the communication equipment that we have, let alone the weapons and tactics, et cetera. But listen, I know you’ll rise to the occasion. So I’m not going to give you any training. I’m just going to drop you right into Syria, and you’ll be fine.” Does anybody think I’ll be fine? No, of course not.

So it’s this funny thing, because on one hand, we’re afraid of the public speaking opportunity, but at the same time, we don’t put a lot of work into it because it’s not a life or death situation. And so then we’re in this conflict of not putting the work into something that actually needs the work, and then we disappoint ourselves and we say, “I don’t want to do it anymore.”

Drew McLellan:

Yeah, and the stakes can be so high for agency folks. I mean, just speaking at a trade show where they have subject matter expertise can literally change the trajectory of their billings for the year with one inquiry or request for a proposal. So the stakes are pretty high. So I want to take a quick break, but when we come back and want to talk to you about a couple times, you’ve referenced the stage and stagecraft and the theatrical nature of presenting. So I want to talk a little bit about that when we come back, because I think that’s a key element to not only getting comfortable on the stage, but also being memorable on the stage. So let’s take a quick break, and then come back and chat about that.

Thanks for checking out this week’s episode of Build a Better Agency. I wanted to interrupt very quickly and just remind you that one of the services that AMI offers is our coaching packages. And it comes in a couple different options. So you can do our remote coaching package where we would communicate with you over the phone or over a Zoom call. Or we also do on site consulting, where we would actually come to your agency and work with you for a day or a period of days to solve a specific problem, typically that you’ve pre-identified, and we’ve talked about on the phone. So if you’re interested in either of those, you might go over to the AMI website, and under the consulting tab, you will find more information about both our remote coaching and our on site consulting.

Let’s get back to the episode. Okay, we are back with Michael Port. And we were chatting about public speaking, however that may be, and public speaking maybe in your office with a couple of people across the desk from you, it may be an all agency meeting, it may be literally on a stage, perhaps at a trade show where you are trying to share your expertise. But before the break, Michael had alluded a couple times to this idea of the theatrics of presenting and how to really improve your performance through stage craft. So talk a little bit about that, Michael.

Michael Port:

I know one of the things that is very counterintuitive is that often authenticity and naturalism when presenting comes from preparation. It seems that it would be less naturalistic the more rehearsed you are, but in fact, the opposite is true because you can give a presentation and walk onto that stage or walk into that meeting room and let everything you know go away, completely blank. And then in the moment, it comes to you authentically, organically, exactly as you planned because you know it’s so well, then the audience feels, “Oh my god, this is happening for the very first time. This is incredible.” But yet it doesn’t feel like it’s being made up.

Everything is intentional. Everything has a purpose. Every story works. Every story has a moral. There’s a lesson that I get it all just comes together. But it feels like it’s happening for the first time. So if you go to watch Hamilton on Broadway, what they’re doing is not something that they just made up that afternoon. It’s exact same way they do it for all eight shows every week, and once in a while someone will be two seconds late for an entrance, or someone will call for a phone go [inaudible 00:33:01] in the audience, and then they’ll have to improvise, but it’s the same thing.

So this marrying of improvisation and preparation is what produces the spontaneity and naturalism. And that’s what the audience is often looking for. Now, if you look at take just the stage for example. And the stage is a place where big things happen, meaning nobody expects, and most audiences do not want pedestrian activities on the stage. They don’t want everyday life on the stage. They want things that are larger than the everyday life that they find themselves in.

So they want big choices made by the performers, and a lot of great speeches live at the intersection of educational content and theatrical elements. So if you took say two circles, and you drew them and you overlapped the side of each circle, and one circle was educational content, and the other circle was theatrical elements, where those circles overlap, that intersection is often what makes a speech really quite remarkable. So Erik Wahl is a great speaker. He probably does 115 big gigs, very, very big gigs a year. And he paints on stage three different times, is very theatrical. And audiences absolutely love his speeches, because it combines this educational content with these theatrical elements of him doing this performance art on the stage. Now, I’m not asking everybody to do.

Drew McLellan:

I was going to say, so for those folks who are not good painters, so examples of what an ordinary person be able to do.

Michael Port:

So, I saw a clip from a TED talk a number of years ago where the speaker was trying to explain to the audience how much oil from the ground, crude oil it takes to make one Big Mac. Now, you could just tell them, or you could show them. So what did he do? He took out a Big Mac, he put it on a table, and he opened up the box. So on the table, it was a real Big Mac and a box. And everybody knows what that looks like. But there it was. And then he took out a glass, and he put it on the table right next to the Big Mac. And then you took out a big pitcher of oil. But it was a see through, clear pitcher. So you can see this black oil in the pitcher.

And he said, “Do you know how much oil it takes to make one Big Mac?” He took the pitcher, and he filled up the glass with oil. And he put the pitcher down and took a beat, which is a pause and he said, “Nope, not that much,” took out another glass, put it on the table, took the pitcher, filled up that second glass, put down the pitcher, said, “No, not that much.” Took out a third glass put it on the table, took the picture, filled up the third glass, put down the pitcher said, “Nope, not that much.” Took out a fourth glass, filled it up halfway, put down the picture and said, “Yep, three and a half glasses of oil to make this one Big Mac.”

Now, I’m pretty sure that that audience had that illustration burned into their minds for the rest of their lives. So he took a statistic, which is how much oil does it take to make one Big Mac? That’s a statistic. It’s a bit of numerical data. And he now illustrated it in a really compelling way that brought it to life because very often, people need to see something in order to really get it. And when I say see, it can mean literally see like this particular example. But also, in order to understand a new concept, sometimes it’s helpful to see another concept that we already understand that is similar so that we can extrapolate the context from one to the other.

And when you show three and a half glasses, everyone is familiar with a glass and the size of a glass and how much is in a glass. And when they saw three and a half, they don’t even know exactly how much that is, were there 12 ounce or 16 ounce glasses? They didn’t care, it didn’t matter. There was still a large amount of oil that they could visually see, and they could connect to because they had some context around, and he made his point very, very well. You could do that in a pitch meeting as an agency creative when you’re trying to explain a new concept.

Drew McLellan:

Right yeah. Yeah, and I think sometimes, again, this gets back to the rehearsal thing is, I think you have to be through the mechanics of it to start thinking creatively about that and go, “Oh, wait, I could show them this.” But if you’re still trying to remember your PowerPoint deck, you’re building the deck the day before you have to give this speech, you don’t have time to say, what would be an interesting way to visually present some of these topics?

Michael Port:

And look, I think most of us would acknowledge that these decks that are used are used in large part as crutches.

Drew McLellan:

Well, they’re your index cards that we’re using [crosstalk 00:38:17] exact kids, right?

Michael Port:

Exactly, that’s what they’ve replaced, big index cards. And so what, often happens when people work on speech is they actually start with a deck, right? They open up PowerPoint or keynote, and they say, “Okay, what slide would I like to put first, the title of it. Okay, so what’s the title, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah.” And then they do that, and then maybe they’ll run through it one or two times in their head or kind of mumble through it and go, alright, good, I’ve got a confidence monitor, I can look at it and see what slide is, and I can speak to that slide. Totally get it. Been there, done that myself.

But generally, the slide decks, if you’re really trying to produce something that is going to make some significant change, those slide decks should be the last thing you’re doing. And I don’t mean last minute trying to throw it together. I mean, that speech is built, that content is built, the speech is written, and then you start to look at, well, what other elements can I add in that are going to help illustrate these points, that are going to make my case even stronger? But if I didn’t have any visuals, could I do it? And then you know you’ve got something really strong because also look, if you present a lot, you know your slides are going to go down at some point, or they’re going to put the wrong deck up, and you’re going to have Sally’s slide deck at your disposal, instead of the one you created.

Everybody who speaks more than a few times a year in an industry, event or something has had some kind of experience where the tech went awry. This way we don’t rely on it and we can work without it. So when you’re starting to work on something, you have your content development phase, and then you have your speech writing phase, because the content development stage is the ideation stage. What are the ideas that I want to bring to people and how am I going to organize them so that I achieve my objectives? Then the next question is, well, how do I create a narrative that I can script so that when I’m delivering this, there’s a through line that connects all of these ideas.

And first thing we look at is the big idea that supports the whole presentation. Now the big idea is the message and it doesn’t have to be different to make a difference. A lot of times when we think big idea people think unique, never before thought of. Not necessarily, a big idea is something that is relevant and important to the people in the room. Simple as that. That’s a big idea, relevant and important. Now, the next thing we want to look at as well, if we know what our big idea is, what’s the promise that we’re making to the audience? Meaning if they adopt this big idea, what’s going to happen?

Okay, now we’ve got those two things, that’s farther along that most people have in most stages. The next thing we want to look at is all right, well, how did these people see the world? Because two things will occur that point number one, if we’re able to really, truly identify and then demonstrate, articulate, illustrate how they see the world, then they are more likely to consider our big idea because when we are approaching a group of people with an idea that they haven’t yet adopted, that idea might be confronting, it might be provocative. It might be something that they are naturally inclined to push back against.

Drew McLellan:

Right, that maybe they don’t want to do it or accept it.

Michael Port:

Yeah, because it might require some change or resources, financial or otherwise that we may not be inclined to commit unless we are highly motivated to do so. So if the audience can say, “Oh yeah, well, I mean, Drew, I get it, that big idea it’s relevant, it’s important, I get it. And I like the promise that you’re suggesting here, but you don’t really understand me. My situation is different.” Then they can say, no, it makes it much easier for them to say no, but if they say, “You know what? Drew, you got me, you totally get me. That’s it. All right, I’m going to listen.” It really does make a difference. That’s one reason.

The second reason being able to articulate, illustrate, demonstrate the way the world looks to the people in the room is because then you can run your big idea and your promise against that worldview and see if it’s actually something that meets up with that world view that marries well with that worldview because it may not. And then you go, “Well, it doesn’t actually fit for these people, so I got to focus on something else because this may not be something that they’re actually that interested in. It might not be that relevant or helpful based on the situation that they’re in right now.”

And then the next two elements to look really clearly at are, well, what are the consequences of not adopting this big idea? What are the consequences of not seeing the world from this perspective? What are the consequences of not achieving this promise? Because very often we’re moved by the pain even before we’re moved by the possibility of the pleasure. And then the fifth element are the rewards, the benefits of actually achieving this promise because we adopted this big idea and we went after it and those rewards may be financial, they may be emotional, they may be physical and they may even be spiritual depending on the kind of work we’re doing.

So that’s the beginning of the ideation process for the content itself. Now, it gets much more involved, but if we have those elements in place, even if you had two days to prepare a presentation internally at the office, if you just focused on those five elements, the big idea, the promise, the way the world looks to the people in the room, the consequences of not adopting the big idea and the rewards from a financial, emotional, physical, and maybe even spiritual perspective of adopting the big idea and achieving that promise, you’d be ahead of 99% of every presentation that exists or is happening right now at this very moment.

Drew McLellan:

Yeah and you haven’t even started your deck, right?

Michael Port:

Exactly.

Drew McLellan:

So, let’s say I’ve done, and it’s interesting as I’ve been listening to you I’ve been hearing our mutual friend Tamsen Webster in my ear talking about the red thread of how you weave all of that through. So I’ve gone through the ideation stage and now I have to construct this narrative. Is there a methodology to doing that? Well, you could do a fable, or you can do a this, you can do a that. When you’re coaching people are there, how do I transition from I’ve identified these sort of facts if you will, this ideation to actually now telling the story on stage, or in the meeting or whatever.

Michael Port:

Yeah, there are a number of different methodologies. And as I said it earlier, I’ll say it again, it’s a mantra for us that there isn’t one way to do this work.

Drew McLellan:

Which I love because a lot of people feel like, well, I could never speak like so-and-so.

Michael Port:

Yeah, and that’s true.

Drew McLellan:

But you don’t have to, right?

Michael Port:

I could never speak like Martin Luther King, that’s just never going to happen. To try would be an exercise in futility. But I can express myself based on the gifts that I have, and based on the amount of work that I’m willing to put into the development of those ideas. So comparing ourselves to others just in general is a really difficult process to go through. And we usually end up on the losing side of any equation where we’re comparing ourselves. Because even if we think we’re better because we did the comparison, we actually feel worse about it because that means we’re putting somebody else down when we think we’re better than them.

So it’s just a losing proposition. And most creative people don’t waste their time with it. They’re just looking at how can I be better than I was the day before? Because you can’t even be the best frankly, which is why things like the academy awards is all very strange to me. There is no one actor who was the best actor of the whole year in a part, that’s not how it works. But that is economically advantageous to the industry. And people like to position themselves as the best and I get that, but I think let’s just be a little bit better than we were the day before. And what we’re doing at HPS is trying to offer methodologies, and practices, and protocols to people that they can use as a way in.

And then if you have these at your disposal, then you can adjust them, you can tweak them for your own sensibility, your own style, what works best for you. But if you don’t have any tools that you can use to get into it in the first place, and you might not even know what you don’t know. So that’s very, very important. Now, answer your question. There are a number of different ways to approach this one way that you can organize information is by frameworks. And there were a number of different frameworks you can use and I’m going to give you some frameworks and then I’m going to give you some books as examples of these frameworks, because most of us have read the same books, but it’s less likely that we’ve seen the same speeches.

And there’s some similarities between books and speeches with respect to the way that they’re organized. So one framework that can be used was very, very straightforward, it might seem a little bit easy, but don’t confuse easy with effective.

Drew McLellan:

Simple is not always easy, right?

Michael Port:

Exactly. Is the numerical framework. Because there are some times where you have a number of keys or a number of rules, or a number of elements, or principles that you feel if you taught a certain group of people would change the way they see the world, would change the way they think, they feel, or act and help produce the objective. So think of Seven Habits of Highly Effective People. Very simple, very simple, one of the best selling business books of all time, or really personal development books of all time. And it’s seven simple principles.

Of course, Stephen Covey is not with us anymore, but if his son or someone from the organization wanted to deliver that material now they don’t have to do all seven principals, they could do one, they could do three, they could do five, or they could do all seven, they don’t even have to go in a particular order. So you have a lot of flexibility when it comes to numerical frameworks. There’s also a sequential or chronological framework, which is usually a series of steps. There’s just some information that is best served when you introduce it in a chronological or sequential form. And so if the material you’re introducing fits that model, it can be very, very effective and any of these models help you remember the content for delivery because now it’s well-structured.

Sometimes there isn’t a massive difference between the expert and the person who has some experience. The big difference often is how well the expert can organize their information. The better organized your information is, often the higher value you bring to an audience which then has them perceive you as a higher value expert. So that’s another framework. And Book Yourself Solid, is the first book that I wrote in 2006, it has multiple additions, there’s an illustrated edition, that book used that sequential framework. There were a series of building blocks that if you put into place in this particular order could then create marketing and sales system for a small business. Very straightforward.

Now, another framework that you can use is the modular. Now, this is less frequently used in speeches, and more frequently used books because modular framework helps you organize a massive amount of information because it helps you then chunk it down into big modules. So Book Yourself Solid also used a modular framework. So these frameworks can be combined because I had so much information that I needed to bring to them. I said, “Okay, well, there are four different modules,” and then there are certain building blocks in each module. Now I want everybody to go through these modules and these building blocks in a sequential fashion, they can be organized together.

One of the big problems that we often find in speeches is that people bring much too much plane for not enough runway. Meaning, content for an entire day, attempted to be delivered in 45 minutes. Why do we do that? Well, we do that because we want to bring value, we want to demonstrate how much we know, we want to make sure that everybody says, “Wow, they brought so much.” And we would rather error on the side of people saying, “I don’t know man, that dude was smart. And men, it was like drinking from a fire hose. I have no idea what the hell he was talking about, but he was really smart.” We’d rather error on that side than the fear of the side of, well, you know he didn’t really seem to know what he was talking about, he didn’t really have that much to add. So we go way to the side-

Drew McLellan:

To the extreme, right?

Michael Port:

Yeah, to the extreme. But really, if you think about most of the great speeches there’s one big idea. And the whole speech is designed to support that big idea.

Drew McLellan:

Which gets back to your ideation to start suggesting.

Michael Port:

Correct, exactly.

Drew McLellan:

[crosstalk 00:51:52] that from the beginning.

Michael Port:

Exactly right. That’s right. So you have the numerical, you have the chronological or sequential, you have the modular, you can also use a compare and contrast framework. So Jim Collins did this with Good to Great, another one of the best selling business books of all time. He said, “Look, here are 10 good companies, and here are 10 great companies. Now, here are the similarities and here are the differences.” So now as a reader of that book or as an audience member in a speech that he gives, I can look at what each one of the companies had that was the same and determine do we have that in place at our company? And then what was the difference? Do we have in place what these great companies actually have in place? Another very effective way of organizing content.

You can also use a problem-solution framework. A problem-solution framework is often very, very effective, especially at the beginning of a development process because if you identify well, here are the problems that the people that I’m attempting to serve face, then what would my solution be for each one of these problems? So there’s a book that a colleague of mine named Mitch Meyerson wrote many, many years ago called Why Parents Love Too Much. And I think this is a great example of this framework because he was a therapist, and he worked with children, and what he found was the kids were okay, it was the parents who were helicopter parents were putting so much pressure on these kids because they loved them so much, that it was actually causing stress and mental health issues for the kids.

So he said, “Look, here are the problems that exist, and here are the solutions for them straightforward.” There are a few other frameworks we probably don’t have time for every single one today but you see those are just ways in, once you start to get into that creative process, you start to breathe some life into it, and then you learn more about what the audience actually needs in order for them to consume that big idea, to process it, and to say, “Yes, I’m going to act on it to go achieve this promise because you understand the way the world looks to me, I really do not want the consequences of not adopting this big idea, but I want the rewards of adopting it. And you know what? I think I can do it because you’ve organized it in a way that my brain can handle, my heart can handle, and I think I’m willing to do it.”

Drew McLellan:

So we hear so much about storytelling. So when you said framework, I thought you were going to go, well, you know what, when you look at Star Wars, there’s the hero and the blah-blah-blah. So where does in the whole idea of this ideation, and the narrative, and the framework, where does the element of not necessarily literally, but where does the element of storytelling play into this?

Michael Port:

Sure. So, storytelling is the easiest thing to sell. It is also I think over emphasized because-

Drew McLellan:

And it’s a little nebulous.

Michael Port:

It’s a little nebulous. And look if someone just took that clip out of context and said, “Look, Michael Port doesn’t believe in storytelling. He doesn’t know what he’s talking about.” No, no, of course look, storytelling is an essential skill to develop. I mean, we work with one of the biggest entertainment companies in the world helping them tell better stories, because the people who create the stories are usually writers, they then have to go pitch those stories verbally, but the best pitches are winning not the best ideas. So we go in there to help them up-level those pitches so that everybody’s ideas gets to see the light of day and the best ideas win, not just the best pitches.

So I obviously believe in story. It’s just, when you see most articles about public speaking, the first bullet point says, tell stories. Of course, they leave off one important detail, which is good stories. Just because something happened to you or you find it interesting doesn’t mean that it’s ready for an audience. To tell a story in front of a group of people in a way that is compelling, that has them on the edge of their seats, takes a lot of sculpting and molding, it takes some time. And if you think about the stories you’ve been telling for 20 years or 30 years.

The story about when you met your spouse, or story about the time you crashed your car when you were 16, you’ve told this story so many times that you’ve been actually rehearsing it, sculpting it, molding it, over time with audiences usually of one, or two, or three, until eventually you figure out what makes it work. Well, without those 20 years of telling it and retelling it again, and again, and again, may not have the same effect. So stories often take a lot more work to work. Then even just a chunk of content that is educational in nature, or even a theatrical bit. So yes, stories are critical, they can make a big difference in your ability to connect with people, certainly.

And you do not have to start a presentation with a story. You do not have to end a presentation with a story. You can, it can be effective, but sometimes when a speaker comes out and starts with a story and the story doesn’t work that well, the audience says, “Oh God, here’s another one of those speeches that starts with a story. All right can we just get through the story and get to the thing I actually want to know? Because that would be helpful.” This is what’s going through their mind sometimes. So when we work on stories, we start with the three act structure because it is the most straight forward approach to storytelling.

The three act structure is not something that I created it’s something that Aristotle defined, but Aristotle didn’t even come up with the structure, he heard people telling stories and he thought, “Well, there seems to be three acts. There’s this exposition, this initial period of information where that we need in order to understand what’s about to happen. Then there’s this second act. And the second act starts with an inciting incident, some sort of conflict is then produced as a result of this inciting incident. And then eventually the story resolves, the conflict resolves in one way or another, it might be a happy ending, or it might not be a happy ending.

Look if it’s a Disney movie, everybody walks happily off into the sunset. If it’s a Quentin Tarantino movie, everyone is dead except the lead character who walks away with a trail of blood following them after having murdered everybody. I mean, everybody’s got their thing. But if you look at stories, great stories live in act two, because the conflict is what’s interesting to a listener, that’s what’s exciting. Because conflict produces what? Action. And action produces what? Conflict. So more conflict produces more action, more action produces more conflict.

Take The Bourne Identity for a minute. The Bourne Identity with Jason Bourne as the lead character played by Matt Damon, it opens with a body floating in an ocean with two bullet holes in his back and the guy’s unconscious. Well, some fishermen take out the bullets from him, he seems to be able to speak their language but he’s not from where they’re from, he also can speak English. Other than that, he knows nothing about himself, nothing. So the exposition that we have is just that, that’s all we have. But every single thing that happens is conflict, action, conflict, action, conflict, action. And through the whole film we’re learning more about him. So more exposition is being exposed to us through the conflict. That’s one of the reasons that film works so well.

And then there’s a little bit of a resolution at the end, but enough that you’re wanting more so they give you a SQL and this goes on for some time. So when you’re thinking about a story, run it through that three act structure. What’s the information that I need to give them so they understand what’s happening? Most stories, if you analyze them, when they’re told by people on stage or off stage have much too much exposition so that the listeners are looking at their watch and thinking, “Is something going to happen?” At some point, sort of like watching a French film, maybe something will happen at some point, I don’t know. I tease the French, the French are easy to tease.

So if you don’t have enough exposition, however, then you’re confused, you don’t understand what’s happening in the conflict. Wait, wait, who’s the sister? Wait, why are they in bed together? I thought they were related, this is weird. So just enough, that’s it. And then we get into act two. So how do you heighten the conflict? Keep raising the stakes. And then the resolution could be, that’s it, done. Maybe there’s a moral to the story, but that’s separate, that’s after the resolution. So storytelling of course, is very, very important, and it’s something will be well-served by working on, but it’s not as easy as one might suggest.

Drew McLellan:

But to your point, it still has to fit in a framework. It still has to serve the idea.

Michael Port:

That’s right.

Drew McLellan:

It still has to serve the purpose of the presentation.

Michael Port:

That’s right. You can tell a great story that is completely ancillary and unrelated to the topic at hand that you’re there to speak on and you do it once and they’ll go, okay, good story let’s get back to the thing, okay that’s good though. You do it more than that. More than once you do it twice, three times, four times, even if the story is great, the audience is going to be disappointed because that’s not what they’re there for. But any story that you tell in a presentation needs to serve the big idea and the promise that you are making with that presentation. You may use a story to help demonstrate that you understand the way the world looks to them. You may use a story to help articulate some of the consequences of not adopting this big idea. You may use a story to help illustrate the rewards because of course stories when they’re well told are really enjoyable to us and we can see ourselves in that story.

Drew McLellan:

Yeah, I feel like we have just scratched the surface of this. Which is why you and Amy do what you do, and it’s why you teach the courses you do and all of that. So two things, first and foremost, thanks for being on the show. And I definitely need to have you back because I have a whole laundry list of questions that we did not get to so.

Michael Port:

Well, thank you so much it is my pleasure. I never take it for granted it’s just a delight to be a part of your show.

Drew McLellan:

Yeah, so awesome. If folks want to learn more about HPS, and the work that you do, and all of that, what’s the best way for them to do that?

Michael Port:

Heroicpublicspeaking.com. Heroicpublicspeaking.com. And send us an email if you want at [email protected]. [email protected] and we’ll answer them.

Drew McLellan:

That’s a beautiful thing. We will include that in the show notes for sure. Michael this has been awesome. Thank you. I love the work that you guys are doing. I love that you make everybody feel like they’re a hero on the stage regardless of the size of the stage. I think it’s a gift that you give for your clients. I know a lot of my folks need to learn more about you so very, very much appreciate your time.

Michael Port:

Thank you so much. Thank you for having me.

Drew McLellan:

You bet. All right guys this wraps up another episode of Build a Better Agency. I’ll be back next week with another guest. Big shout out and thanks to our friends at White Label for being the presenting sponsor. Remember to check out whitelabeliq.com/ami because they’ve got a great deal for you. If you’re trying to track me down, it’s [email protected]. I’ll be with you next week. Thanks.

Speaker 4:

Thanks for spending some time with us. Visit our website to learn about our workshops, owner peer groups, and download our salary and benefits survey. Be sure you also sign up for our free podcast giveaways at agencymanagementinstitute.com/podcast giveaway.